|

Different uses for voting

need different types of voting. |

|

Fair-Share Ballots |

|

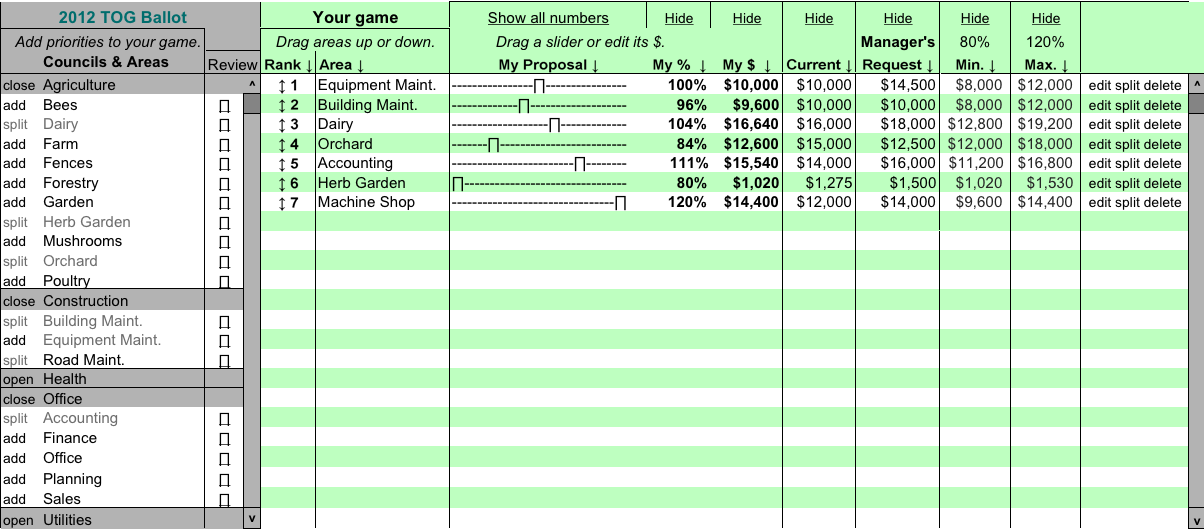

Note: This page is about how to make each voter's first choice count more than their second choice, etc. This is a good feature but it is not essential. When each voter's share of money can pay for just a small fraction of the least costly project, then a voter may give their whole share to one item. A previous page explained this. Ballots for Fair-Share SpendingRanking project proposals is as easy as 1, 2, 3. But even that can be hard when there are dozens of proposals. Some voters agonize over making a precise list with a unique rank for each item. Voters should know that the rule lets you skip a rank or use it twice for items you feel are tied. But some people worry that such a loose ranking is not proper or powerful. Dr. Robert Tupelo-Schneck created the best MMV ballot. “You can log in as anything, and press Continue four times to get to the actual ballot. This particular allocation was a little unusual in that the organization was allocating cuts to existing budgets after an income shortfall---basically a negative allocation. But the principles are the same.” It lets you simply slide items up and down your list of preferences and also set new budget levels.

Sometimes pc voting booths are too expensive or too slow because there are not enough of them. In that case voters can use paper ballots, and clerks can enter and double check those for a computer tally. Even on a "rank ballot," a few people in any large group think a bigger number is better. So they give big numbers to their favorites. They are more likely to get what they want with ballots that grade the items. Voters can pencil in dots on a "bubble-form" paper which is read by an optical scanner. The ballot shown here lets a voter grade items from A++ to F- -. That allows 30 different grades; so a voter can choose up to 30 levels of preference on the ballot. |

Powerful Ballot Made EasyFor voters to have power, they need ballots that make it easy to rank many options.

Instructions for the Trade-Off Game

|

An Advanced Tally with Movable Money VotesThis demonstration follows an introduction to Single Transferable Vote, which may include an STV workshop with tabletop voting.

[As audience answers, look for these points and more.] Let's say the quota is ten; that means to win public funds, an item must have strong support from at least ten council members. So one rep may contribute only one-tenth of a project's budget.

One-tenth of a low-cost project will be less than one rep's share.

Now, I could just hold on to the remainder of my share, as I watch each of my lower choices fall into last place and get dropped. Or I could offer some of my money to my second and third choices. It makes sense to help them avoid elimination.

But how much should I help lower choices? I don't want my vote for a lower choice to prevent its elimination, if that means my first will be eliminated. So I have the option that my lower choices will not count if my first choice is the weakest candidate. Likewise, if my second is threatened with elimination, my votes below that temporally do not count. So helping a lower choice never threatens a higher choice.

( The option to protect favorites has a down side: While hiding lower-choice votes, I'm helping fewer items. So I might see some of my lower choices eliminated and then see my favorite eliminated anyway.) OK.

If my second choice is eliminated, [Remove its money.] others move up. [Slide column three next to column one.] Then my ballot transfers that money to my next choice. [Spread the money in a new third column.] That's a transferable-vote rule for projects. Any questions up to this point?

We can make a tally even better at funding favorite projects.

The more expensive the project, the wider its column. Here's a low-cost project with a narrow budget, and to the right a costly project with a wide budget. My offers to my favorite projects use up all of my share of money. I would like to give my first choice more than one vote. That will help it win.

The tradeoff is that lower choices get less than one vote. Is it obvious that this will help fund first-choice items? Does it seem fair to move money so the first choice gets two votes and a lower choice get only a half vote? . . . ( This is also a way to protect favorites. It is a compromise between leaving my favorite vulnerable to my votes for lower choices, versus leaving lower choices with no votes.) Of course, to make the quota work, the rules limit the number of votes I may give any one project. A good limit is two votes. Now the height of the first column changed and the height of the others changed. What quantity is constant on this table? . . . Right, the money! One share, that is the area covered by my money. The width of an item's column(s) is also constant; the width is one-tenth of the budget the item should get. ( Note that the total width also equals one share, forcing me to spread out my money. If I could concentrate my influence by giving the maximum vote to as many items as I could afford, it would, in effect, reduce the quota. Again I would not be helping my first any more than my third -- so the tally might end up funding the third choices instead of the first choices.) How a Hands-on Ballot Spreads a ShareThe workshop introducing transferable votes gives the easiest example: Each project gets one column for every $100... in its price. Each voter gets a bag of cards, tokens for his share of the funds. The bag holds small, medium and large cards. He puts his largest card in the first column of his favorite project, and he may give more than one card to an expensive project with more than one column. A project wins if voters fill all its columns.

A picture of cards, lined up by size, graphs the funding "utility" curve inherent in each bag of cards. These 6 cards are made of 12 alphabet blocks and the average card, with 2 blocks in this case, counts as 1 vote. A computer tally of the most basic type is like a workshop's tally board. The program gives a ballot dozens of 'cards', with slightly different values. It puts the biggest card in the first column of the voter's favorite item. Then the second-biggest card goes in the item's next column, if it has more than one. After the ballot has put one of its cards in each column of the favorite item, then it offers the next, slightly-smaller card, to the first column of the voter's next-favorite project.

The next page adds some options for the tally and how a ballot apportions money, labor or other resources among a voter's top-rated items. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Accurate Democracy

Accurate Democracy